* Tap On The Photo to Enlarge

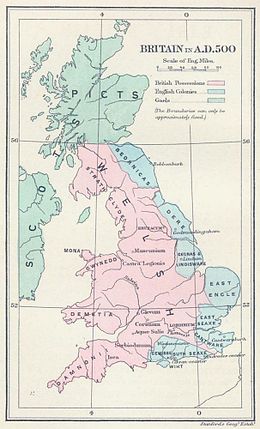

From the departure of the Romans in the fifth century AD and the arrival of the Normans in 1067, Wales was an independent country. In this period Wales was divided into a number of small kingdoms, often at war with one another and with their Anglo-Saxon neighbours. It had its own church, language literature and

culture.

During this period Norsemen attacked communities along the coast. They also established trading links, and left a legacy of place-names such as Skomer, Skokholm, Bardsey and Anglesey.

Early medieval Wales was a colle ction of small kingdoms. These were proud of their independence, while clearly subordinate to English kings, like Edgar and Athelstan. These kingdoms enjoyed a rich literary culture. Their language was Welsh and the bardic tradition was especially valued, with poets travelling from community to community telling stories, and reciting poems celebrating figures such as Arthur and Merlin.

ction of small kingdoms. These were proud of their independence, while clearly subordinate to English kings, like Edgar and Athelstan. These kingdoms enjoyed a rich literary culture. Their language was Welsh and the bardic tradition was especially valued, with poets travelling from community to community telling stories, and reciting poems celebrating figures such as Arthur and Merlin.

One of the most powerful kings of early Medieval Wales was Rhodri Mawr ('Rhodri the Great') of Gwynedd (d.877). Rhodri established the main royal line of Welsh kings - Gwynedd - which continued until1283.

Hywel Dda ('Hywel the Good'), king of Dyfed (d.950) established a code of law for the whole of Wales. He was a frequent visitor to the English royal court, and visited Rome in 928.

Gruffudd ap Llywelyn (d.1063) was a fierce warrior who brought Wales under his rule, but his command of the whole country came to an end when he was defeated by king Harold Godwinsson of England.

Dramatic change came with the Norman Conquest of England (1066) and the arrival of the Normans in Wales the following year. William I ('the Conqueror') planted powerful Norman lords along the border with England and these soon made massive incursions into Wales from bases like Chester, Shrewsbury, Hereford and Gloucester. The Norman armies soon captured the fertile valleys and lowlands of Wales, taking advantage of the rivalries between the Welsh kings. They built castles at places such as Chepstow, Cardiff, Brecon, Abergavenny, Neath, Swansea, Pembroke and Cardigan. They established boroughs around these castles, the main ones being at Chepstow, Caerleon, Cardiff, Brecon and Rhuddlan.

These lands along the English border, and incorporating the conquered Welsh territories, became known as the March. The Welsh still controlled the mountainous heartland of the country, but were always under threat from the Marcher lords and the English crown.

In 1081, King William came on pilgrimage to St. David's and recognised Rhys ap Tewdwr as king of Deheubarth in south-west Wales. However, Rhys ap Tewdwr was killed in battle near Brecon in 1093. This left the status of Deheubarth and the other major kingdoms of Gwynedd and Powys in jeopardy.

Wales still presented the Normans with serious challenges. The topography of the nation was one such challenge and the mountains provided a refuge for insurgents. The numerous Welsh kingdoms meant that each would need to be conquered in turn - a single victory could not secure the whole of Wales for the invaders. The Norman barons also held lands in England and France and, crucially, owed service to their king. This meant the time they could devote to their territory in Wales was limited.

The balance of power between the Norman barons and their king was of

critical importance during this period and this had an impact on the history of Wales. When the English king was strong (William I, Henry I, Henry II, Edward I) the Welsh needed to be cautious, but with a weak English king (William II, Stephen) the Welsh were emboldened to challenge the Norman dominance of their country. Two kings (John, Henry III) enjoyed periods of strength, but at other times were weakened - allowing the Welsh to challenge.

Outside the areas controlled by the Marcher barons were territories held by Welsh princes and lesser lords. The great principalities were those of Gwynedd, Powys and Deheubarth (south-west Wales). Princes and Marcher lords alike were expected to pay homage to the king of England.

Monastic orders from France, first the Benedictines and then the Cistercians, built impressive monasteries and priories in Wales.

Boroughs were established around the castles largely populated by the Anglo-Normans, These boroughs and the surrounding lands became known as the Englishry. These communities were answerable to Anglo-Norman law, and the lands were organised along manorial lines. The surrounding areas, largely hilly, were known as the Welshry. These were populated by the indigenous Welsh, who continued their traditional way of life. Commerce ensured some social mixing between the two communities. Although Welsh law prevailed in the Welshries, they were also subjected to harsh and discriminatory laws by the Anglo-Normans, which left them with second-class status within their own country.

Fierce battles between the Welsh princes and the Normans/English characterised this period. To gain power, Welshmen were prepared to blind, castrate or murder, those who frustrated their ambitions - in a number of cases, their own relatives. Between 1075 and 1197, of the 24 men of the dynasty of Powys fourteen were killed or maimed; this bloodlust was shared by English kings and Marcher lords, as evidenced by the fates of Edward II and Hugh le Despenser.

The vicious rivalry between brothers can be explained by the Welsh law of succession - ownership of land went by partible succession between sons or other males (no woman could own land). The kingdom of Deheubarth, which was held by the great Lord Rhys (d.1197), was broken up after his death by infighting between his eight legitimate and seven illegitimate sons.

An uneasy truce was established when the English crown recognised that to conquer the principalities would be too costly, and unlikely to be permanent. Anglo-Norman lords intermarried with Welsh royal families; two daughters of English kings - illegitimate, but richly endowed - were married to Welsh princes. Nest, the daughter of Rhys ap Tewdwr, became the mistress of Henry I but was abducted by the brave (foolhardy?) Owain ap Cadwgan, prince of Powys.

This was a period of great social and cultural change. A significant figure to challenge the Anglo-Norman hegemony was Gruffudd ap Cynan (d.1137) who fought bravely for decades to re-establish the kingdom of Gwynedd as the dominant Welsh kingdom. He was incarcerated in Chester prison for a decade before making a dramatic escape. His son Owain Gwynedd (d.1170) secured lands in north-east Wales from the English almost to the river Dee, and helped Gruffudd ap Rhys of Deheubarth defeat the English in battle near Cardigan in 1136.

Owain Gwynedd and Rhys ap Gruffudd (d.1197), also known as Yr Arglwydd Rhys ('The Lord Rhys') of Deheubarth, collaborated to frustrate Henry II's ambitions in 1164, and they both built castles. Rhys held a festival of music and poetry in Cardigan Castle in 1176, which is now recognised as the first eisteddfod.

The principality of Powys extended from the south-east of Gwynedd to Deheubarth in the south. It was subjected to considerable pressure from the powerful principality of Gwynedd and the Marcher lords. It succumbed to these pressures and broke up by the end of the twelfth century.

After Owain Gwynedd's death in 1170 Gwynedd's power declined for 30 years. However, his grandson Llywelyn Fawr ('the Great') -d.1240 - restored Gwynedd to its pre-eminence and extended Gwynedd's power throughout Wales. He took advantage of the weakness of king John of England, who was challenged by rebellious barons (many of them allies of Llywelyn). He proceeded to capture the castles of Carmarthen, Cardigan and Montgomery.

Llywelyn exercised considerable diplomatic skills as well as showing military prowess. He married Joan (Siwan), the daughter of king John of England, and she became a trusted ambassador to the court of England. His four daughters married Marcher lords. His son Dafydd married Isabella de Braose despite Llywelyn having hanged her father in 1230 for cuckolding him with Siwan.

Dafydd (d.1246), Llywelyn's only heir, was childless so the principality fell to Henry III of England. It was left to Llywelyn's grandson Llywelyn ap Gruffudd ('Llywelyn the Last') to re-establish Wales' claim to independence. He was a great warrior, and he overcame challenges from his brothers to rebuild and extend the power of Gwynedd, and other Welsh lords became his vassals. In 1267 Henry III of England signed a treaty acknowledging Llywelyn as Prince of Wales.

Llywelyn, however, had his problems. His brother Dafydd was an unreliable ally. In Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn of Powys he had an implacable enemy. He alienated Henry III's son Edward (the future king) by defeating him in battle. The Welsh lords of the uplands of Glamorgan decided to support the powerful Gilbert de Clare, builder of Caerffili castle. He also fell out with the Bishops of  St. Asaph and Bangor.

St. Asaph and Bangor.

Llywelyn taxed his people heavily to pay for new castles at Dolforwyn and Ewloe. He refused to pay homage to Edward 1 of England, and did not pay money he had promised under treaty. He did not produce an heir.

The king declared Llywelyn an outlaw in 1277 and a powerful attack (aided by some of Llywelyn's vassals) resulted in Gwynedd's surrender. Llywelyn now held only the part of Gwynedd west of Conwy. He married Eleanor de Montfort, a noble French bride. Edward began work on a chain of great castles: Fflint, Rhuddlan, Builth and Aberystwyth.

The Welsh soon realised that Edward's regime was even more severe than Llywelyn's. His brother Dafydd rose in rebellion in Easter 1282 and much of Wales joined the revolt, with Llywelyn at its head. Edward sent armies into Wales trapping Llywelyn in Snowdonia and demanding the total surrender of Gwynedd. The Welsh were determined to oppose the tyranny of the English and Llywelyn managed to escape from Snowdonia to rally supporters in mid-Wales. He and his men were besieged at Cilmeri, near Builth, on 11 December 1282 and Llywelyn was killed. His brother Dafydd was taken prisoner and executed the following year.

Edward captured the lands in north Wales previously held by the princes of Gwynedd and tightened his hold on them by building a number of powerful castles, notably at Caernarfon, Conwy and Harlech. Boroughs were established around the castles peopled by English traders and craftsmen and their families. These boroughs were subject to English laws and government. In 1284, the Statute of Rhuddlan was declared, which stated that Wales would be subject to the English common law (but with some provision for recognition of Welsh law).

Gwynedd was divided into three shires - Môn (Anglesey), Caernarfon and Meirionydd. These were regulated along similar lines to English shires. These three shires, together with Fflint in north-east Wales and the counties of Carmarthen and Cardigan in south-west Wales became known as the Principality. For over 250 years (1284 - 1536) Wales was divided in two - the Principality and the March. Further revolts took place in 1287 and 1294, which resulted in a return of Edward's army to Wales and the building of Beaumaris castle.

The next century saw fewer armed conflicts, but was also a very troubled one. In 1348 the Black Death arrived leading to the loss of a third of the country's population. The plague returned in 1361, 1369, 1379 and 1391.

In 1301 Edward I declared his son, Edward, Prince of Wales and gave him charge of the Principality. When Edward I died in 1307 and his son Edward took the throne there was a dramatic change; Edward II was weak and unpopular. He was captured near Neath, returned to captivity in England and came to an ignominious end at Berkeley Castle in 1327.

During this century the lot of the Welsh was dire. While the English boroughs flourished, the Welsh suffered from discriminatory laws and taxes and became second-class subjects in their own country. In the past the Welsh bishops had been appointed to Welsh diocese, but from 1372 to 1400 of the 16 bishops appointed only one was Welsh.

As discontent with their lot festered, there was an intense yearning for a Mab Darogan ('Son of Prophesy'), who would release the Welsh from their bondage. For many, the obvious candidate for this role was the last heir in the main line of the princes of Gwynedd, Owain ap Thomas known as Owain Lawgoch ('Owain of the Red Hand'). Owain was the great-nephew of Llywelyn Fawr ('Llywelyn the Great'). Owain was a fierce warrior in the service of the French king, and known across Europe for his prowess on the field of battle. The English crown recognised his threat and employed the Scot John Lamb as a spy, and sent him to assassinate Owain at Mortagne-sur-Gironde in 1378.

The search for another Mab Darogan ('Son of Prophesy') came to a climax in 1400 when Owain ap Gruffudd Fychan (Owain Glyndŵr) was declared Prince of Wales by his followers. Glyndŵr was well qualified for the title as he was a direct descendant of the houses of Powys and Deheubarth, and had strong links with the house of Gwynedd. This was a bold challenge to the English crown, and an uprising against English domination followed. By 1405 almost all of Wales was under his control, and he had captured and held Harlech and Aberystwyth castles. He held two Welsh Parliaments. His plans for two universities and an independent Church for Wales were communicated to the king of France in the Pennal Letter (Glyndŵr had strong diplomatic links with France, who provided him with some military support). By 1410, however, Glyndŵr's campaign had declined; he was forced into hiding, and died in 1415.

For full coverage of Glyndŵr's history please use the link: Glyn Dŵr History

The medieval period ended seventy years later when a Welsh-born king, claiming descent from the house of Gwynedd, became Henry VII of England and established the Tudor dynasty.

In the two centuries following the departure of the Romans (383 A.D) Wales developed as a nation. The Welsh language evolved from Brythonic after the Romans left. Before the arrival of the Romans, Brythonic was spoken from the Forth/Clyde region in the north to the English Channel in the south. The first poems in Welsh that we know of come from Strathclyde.

*

About 600 A.D. the masterpieces of Aneurin and Taliesin were written, centuries before written literature in French, Spanish or Italian. Brythonic/Welsh names are seen in England and Scotland, e.g. Cumbria is synonymous with Cymru; Malvern is Moel Fryn; Melrose is Moel Rhos, etc. Communities of Welsh speakers lived in Herefordshire, Worcestershire, Gloucestershire and Shropshire until the nineteenth century.

Wales in the Middle Ages