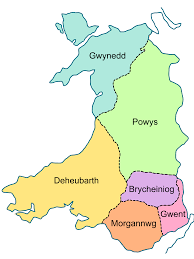

From the depa rture of the Romans in the fifth century AD and the arrival of the Normans in 1067, Wales had been an independent country. In this period Wales was divided into a number of small kingdoms, often at war with one another and with their Anglo-Saxon neighbours. It had its own church, language, literature and culture.

rture of the Romans in the fifth century AD and the arrival of the Normans in 1067, Wales had been an independent country. In this period Wales was divided into a number of small kingdoms, often at war with one another and with their Anglo-Saxon neighbours. It had its own church, language, literature and culture.

Dramatic change came with the Norman Conquest of England and the arrival of the Normans in Wales in 1067. William I ('the Conqueror') planted powerful Norman lords along the border with England and these soon made massive incursions into Wales from bases like Chester, Shrewsbury, Hereford and Gloucester. The Norman armies soon captured the fertile valleys and lowland s of Wales, taking advantage of the rivalries between the Welsh kings. They built castles at places such as Chepstow, Cardiff, Brecon, Abergavenny, Neath, Swansea, Pembroke and Cardigan. These lands along the English border and incorporating the conquered Welsh territories became known as the March. The Welsh still controlled the mountainous heartland of the country, but were always under threat from the Marcher lords and the English crown.

s of Wales, taking advantage of the rivalries between the Welsh kings. They built castles at places such as Chepstow, Cardiff, Brecon, Abergavenny, Neath, Swansea, Pembroke and Cardigan. These lands along the English border and incorporating the conquered Welsh territories became known as the March. The Welsh still controlled the mountainous heartland of the country, but were always under threat from the Marcher lords and the English crown.

Boroughs were established around the castles largely populated by the Anglo-Normans. These boroughs and the surrounding lands became known as the Englishry. These communities were answerable to Anglo-Norman law, and the lands were organised along manorial lines. The surrounding areas, largely hilly, were known as the Welshry. These were populated by the indigenous Welsh who continued their traditional way of life. Commerce ensured some social mixing between the two communities. Although Welsh law prevailed in the Welshries, they were also subjected to harsh and discriminatory laws by the Anglo-Normans, which left them with second-class status in their own country.

Resistance to the Anglo-Norman occupation came from south-west Wales under princes of Deheubarth, north-east Wales under the princes of Powys, but most powerfully from the princes of Gwynedd in north-west Wales. Princes of Gwynedd were keen to extend their power and influence by uniting lesser princes under their control and challenging Anglo-Norman hegemony. The greatest of the princes of Gwynedd were Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, known as Llywelyn Fawr ('Llywelyn the Great'), (1173 - 1240), and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, known as Llywelyn ein Llyw Olaf ('Llywelyn the Last'), (1247 - 82). As well as being fine military leaders, they also possessed impressive diplomatic skills and both came close to establishing control over the greater part of Wales. Llywelyn ap Gruffudd was acknowledged as Prince of Wales by Henry III of England in t he Treaty of Montgomery in 1267. Henry's successor, Edward I (1272 - 1307) was arguably the strongest and most ruthless of English kings and rejected Llywelyn's princely status. Llywelyn was killed in an ambush in 1282, and his brother Dafydd was executed in Shrewsbury in 1283. With Dafydd's death, the line of the great princes of Gwynedd came to an end. Other notable figures of medieval Wales up to this point were Rhodri Mawr ('Rhodri the Great') (d.877), Hywel Dda ('Hywel the Good') (d.950), Gruffudd ap Llywelyn (d.1063), Gruffudd ap Cynan (d.1137), Owain Gwynedd (d.1170) and Rhys ap Gruffudd, also known as Yr Arglwydd Rhys ('The Lord Rhys')(d.1197).

he Treaty of Montgomery in 1267. Henry's successor, Edward I (1272 - 1307) was arguably the strongest and most ruthless of English kings and rejected Llywelyn's princely status. Llywelyn was killed in an ambush in 1282, and his brother Dafydd was executed in Shrewsbury in 1283. With Dafydd's death, the line of the great princes of Gwynedd came to an end. Other notable figures of medieval Wales up to this point were Rhodri Mawr ('Rhodri the Great') (d.877), Hywel Dda ('Hywel the Good') (d.950), Gruffudd ap Llywelyn (d.1063), Gruffudd ap Cynan (d.1137), Owain Gwynedd (d.1170) and Rhys ap Gruffudd, also known as Yr Arglwydd Rhys ('The Lord Rhys')(d.1197).

Edward captured the lands in north Wales held by the princes of Gwynedd and tightened his hold on them by building a number of powerful castles, notably at Caernarfon, Conwy and Harlech. Boroughs were established around the castles peopled by English traders and craftsmen and their families. These boroughs were subject to English laws and government.

Gwynedd was divided into three shires - Môn (Anglesey), Caernarfon and Meirionydd. These were regulated along similar lines to English shires. These three shires, together with Fflint in north-east Wales and the counties of Carmarthen and Cardigan in south-west Wales became known as the Principality. For over 250 years (1284 - 1536) Wales was divided in two - the Principality and the March. In 1301 Edward I proclaimed his eldest son Prince of Wales and gave him charge of the Principality.

During this period of occupation many Welshmen served in the armies of English kings - they were famed for their skills as longbow men. They contributed substantially to English victories at the battles of Creçy (1346) and Poitiers (1356).

The Welsh were subjected to discriminatory laws and taxes, and bristled at being abused by self-seeking English officials. In the past the usual practice had been to appoint Welsh bishops to Welsh diocese, but from 1372 to 1400 of the 16 bishops appointed only one was Welsh. In 1348 the Black Death arrived leading to the loss of a third of the country's population. The plague returned in 1361, 1369, 1379 and 1391.

As discontent with their lot festered, there was an intense yearning for a Mab Darogan ('Son of Prophesy'), who would release the Welsh from their bondage. This yearning was given voice by the poets who served the uchelwyr (gentry). For many, the obvious candidate for this role was the last heir in the main line of the princes of Gwynedd, Owain ap Thomas known as Owain Lawgoch ('Owain of the Red Hand'). Owain was a fierce warrior known across Europe for his prowess on the field of battle who was an officer in the French army. The English crown recognised his threat and employed the Scot John Lamb as a spy, and sent him to assassinate Owain at Mortagne-sur-Gironde in 1378.

The search for another Mab Darogan (Son of Prophesy) came to a climax in 1400 when Owain ap Gruffudd Fychan, (Owain Glyndŵr) was declared Prince of Wales by his followers. Glyndŵr was well qualified for the title, as he was a direct descendant of the houses of Powys and Deheubarth, and had strong links with the house of Gwynedd. This was a bold challenge to the English crown, and an uprising against the English followed. By 1405 almost all of Wales was under his control, and he had captured and held Harlech and Aberystwyth castles. He held two Welsh Parliaments. His plans for two universities and an independent Church for Wales were communicated to the king of France in the Pennal Letter (Glyndŵr had strong diplomatic links with France, who provided him with some military support). By 1410, however, Glyndŵr's campaign had declined; he was forced into hiding and died in 1415.

For full coverage of Glyndŵr's history please use the link: Glyn Dŵr History

The medieval period ended thirty years later when a Welsh-born king, claiming descent from the house of Gwynedd, became Henry VII of England and established the Tudor dynasty.

A Brief Summary