The

Curriculum for Wales, Welsh History and Citizenship, and the Threat

of Embedding Inequality

By Martin Johnes, Hanes

Cymru - June 3, 2020

Welsh education is heading towards its biggest shake

up for two

generations. The new Curriculum for Wales is intended to place responsibility for what pupils are

taught with their teachers. It does not specify any required

content but instead sets out ‘the

essence of learning’ that should underpin

the topics taught and learning activities employed. At secondary school, many traditional

subjects will be merged into new

broad areas of learning. The curriculum is intended to produce ‘ambitious and capable learners’ who are

‘enterprising and creative’,

‘ethical and informed citizens’, and ‘healthy and confident’.

Given how radical this change potentially is, there has been

very little public debate about

it. This is partly rooted in how

abstract and difficult to understand the curriculum documentation is. It is dominated

by technical language and abstract ideas and there is very little

concrete to debate. There also seems

to be a belief that in science and maths very little

will change because of how those subjects are based on

unavoidable core knowledges. Instead, most of the public discussion that has occurred

has centred on the position of Welsh history.

The focus on history is rooted

in how obsessed

much of the Welsh public sphere (including myself) is by questions of identity. History is central to why Wales is a nation and thus has long been promoted by those seeking is develop a Welsh sense of nationhood. Concerns that

children are not taught enough Welsh history are longstanding

and date back to at least the 1880s. The debates

around the teaching of

Welsh history are also inherently political. Those who believe in

independence often feel their political

cause is hamstrung by people being unaware

of their own history.

The new curriculum

is consciously intended to

be ‘Welsh’ in outlook and

it requires the Welsh context

to be central to whatever subject matter is delivered. This matters most in the Humanities where the Welsh context is intended to be delivered through activities and topics that join together

the local, national and global. The intention is that

this will instil in them

‘passion and pride in themselves, their communities and their country’. This quote comes

from a guidance document for schools

and might alarm those who fear

a government attempt at

Welsh nation building. Other documents are less celebratory

but still clearly Welsh in outlook. Thus the goal stated in the main documentation is that learners should ‘develop a strong sense of their own identity and well-being’, ‘an understanding

of others’ identities and make connections with people, places

and histories elsewhere in Wales and across the world.’

A nearby slate

quarry could thus be used to teach about

local Welsh-speaking culture, the Welsh and British industrial

revolution, and the connections

between the profits of the slave trade and the historical local economy. This could

bring in not just history, but

literature, art, geography and economics too. There is real potential for exciting

programmes of study that break down subject boundaries and engage pupils with

where they live and make them

think and understand their community’s connections with Wales and the wider world.

This

is all sensible but there remains a vagueness around the underlying concepts. The Humanities section of the curriculum speaks of the need for ‘consistent

exposure to the story of learners’ locality and the story of Wales’. Schools are asked to ‘Explore

Welsh businesses, cultures,

history, geography, politics, religions and societies’. But this leaves considerable

freedom over the balance of focus and what exactly ‘consistent

exposure’ means in practice. If schools want to minimize the Welsh angle in favour of the British or the global, they will

be able to do so as long as

the Welsh context is there.

It is not difficult to imagine

some schools treating ‘the story of Wales’ as

a secondary concern because that is what already sometimes

happens.

The existing national curriculum requires local and Welsh history to be ‘a focus of the study’ but, like

its forthcoming replacement, it never defines very closely

what that means in terms

of actual practice. In some schools,

it seems that the Welsh perspective is reduced to a tick box exercise

where Welsh examples are occasionally employed but never

made the heart of the history programme. I say ‘seems’ because

there is no data on the proportion of existing pre-GCSE history teaching that is devoted to Welsh history. But all the anecdotal evidence points to Wales often not being at the heart of what history is taught, at least in secondary schools.

At key stage 3 (ages 11 to 14) in particular, the Welsh element can

feel rather nominal as many children learn

about the Battle of Hastings, Henry VIII and the Nazis.

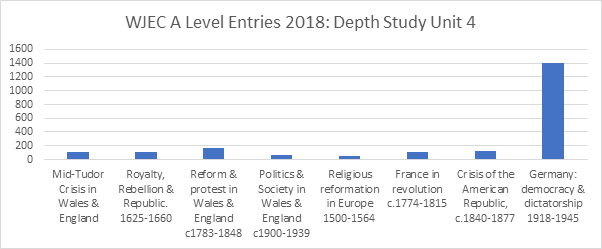

GCSEs were reformed in 2017 to ensure Welsh history is not marginalised but at A Level the options schools choose reveal a stark preference in some

units away from not just Wales but Britain too.

Why schools chose not to teach more Welsh history is a complex issue. Within a curriculum that is very flexible,

teachers deliver what they are

confident in, what they have

resources for, what interests them and what they

think pupils will be interested in. Not all history teachers have been

taught Welsh history at school or university and they thus perhaps prefer to lean towards those topics

they are familiar with. Resources are probably

an issue too. While there

are plenty of Welsh history resources out there, they

can be scattered around and

locating them is not always easy. Some

of the best date back to the 1980 and 90s and are

not online. There is also amongst both

pupils and teachers the

not-unreasonable idea that Welsh history is simply not as interesting as themes such as Nazi Germany. This

matters because, after key stage

3, different subjects are competing for

pupils and thus resources.

The new curriculum

does nothing to address any of these issues

and it is probable that it will not do much to enhance the volume of Welsh history taught beyond the local level. It replicates the existing curriculum’s flexibility with some loose requirement

for a Welsh focus. Within that flexibility,

teachers will continue to be guided by their existing knowledge, what resources they already have, what

topics and techniques they already know

work, and how much time and confidence

they have to make changes. Some

schools will update what they

do but in many there is a very real possibility that not much will

change at all, as teachers simply mould the tried and tested existing curricular into the new model. No change is always

the easiest policy outcome to follow. Those schools that

already teach a lot of

Welsh history will continue to do so. Many of those that

do not will also probably carry on in that

vein.

Of course, a system designed to allow different curricula is also designed to produce different outcomes. The whole point of the reform is for schools to be different to one another but there

may be unintended consequences to this. Particularly in areas where schools

are essentially in competition with each other

for pupils, some might choose

to develop a strong sense of Welshness across all subject areas because they

feel it will appeal to local parents and local authority funders. Others might go the opposite way for

the same reasons, especially in border areas where attracting

staff from England is important. Welsh-medium schools are probably

more likely to be in the former group and English-medium schools in the latter.

Moreover,

the concerns around variability do not just extend to issues of Welsh identity and history. By telling schools they can teach what they feel

matters, the Welsh Government

is telling them they do not have to teach, say, the histories of racism or the Holocaust. It is unlikely that any school

history department would choose not to teach what Hitler

inflicted upon the world but they

will be perfectly at liberty to do so; indeed, by enshrining their right to do this, the Welsh Government is saying it would be happy for any

school to follow such a line. Quite how that

fits with the government’s endorsement of Holocaust Memorial Day and Mark Drakeford’s reminder of the importance of remembering such genocides is unclear.

There are other policy

disconnects. The right to vote in Senedd elections has been

granted to sixteen- and seventeen-year-olds. Yet the government has decided against requiring them to be taught anything specific about that institution, its history and how Welsh democracy works. Instead, faith is placed in a vague requirement

for pupils to be made into informed

and ethical citizens.

By age 16, the ‘guidance’ says learners should

be able to ‘compare and evaluate local, national and global governance systems, including the systems of government and democracy in Wales, considering their impact on

societies in the past and present, and the rights and responsibilities of citizens in Wales.’ Making Wales an ‘including’ rather than the

main focus of this ‘progression step’ seems to me to downplay its importance. Moreover, what this sentence actually means in terms of class

time and knowledge is up to schools and teachers. Some pupils will be taught lots about

devolved politics, others little. The government is giving young people the responsibility of voting but avoiding its

own responsibility to ensure they are

taught in any depth what

that means in a Welsh context.

The new curriculum

will thus not educate everyone in the same elements of political citizenship or history because it is explicitly designed to not do so. Just as they

do now, pupils will continue to leave schools with

very different understandings of what Wales is, what the Senedd does and how both fit into British, European and global contexts. Perhaps that does not matter if we want pupils to make up their

own minds about how they

should be governed. But, at the very least, if we are

going to give young people the vote, surely it is not too much to want them to be told where it came from,

what it means, and what it can do.

But this is not the biggest missed opportunity of the curriculum. Wales already has an educational

system that produces very different outcomes for those

who go through it. In 2019, 28.4% of pupils eligible for free

school meals achieved five A*-C grade GCSEs, compared

with 60.5% of those not eligible. In 2018, 75.3% of

pupils in Ceredigion hit this level,

whereas in Blaenau Gwent only 56.7% did. These are staggering differences that have nothing to do with the curriculum and everything to do with how poverty impacts

on pupils’ lives. There is nothing in the new curriculum that looks to eradicate

such differences.

Teachers in areas with

the highest levels of deprivation face a daily struggle to deal with its

consequences. This will also impact

on what the new curriculum can achieve in their

schools. It will be easier to develop innovative programmes that take advantage

of what the new curriculum can enable in schools where

teachers are not dealing with the extra demands of pupils who have

missed breakfast or who have difficult

home lives. Fieldtrips are easiest in schools

where parents can afford them. Home

learning is most effective in homes with

books, computers and internet access. The very real danger of the new curriculum is not what it will or will not do for Welsh citizenship and history but that it will

exacerbate the already significant difference between schools in affluent areas

and schools that are not. Wales needs less difference between its schools,

not more.

Martin Johnes is Professor of History at Swansea University.

This essay was first published in the Welsh Agenda (2020).